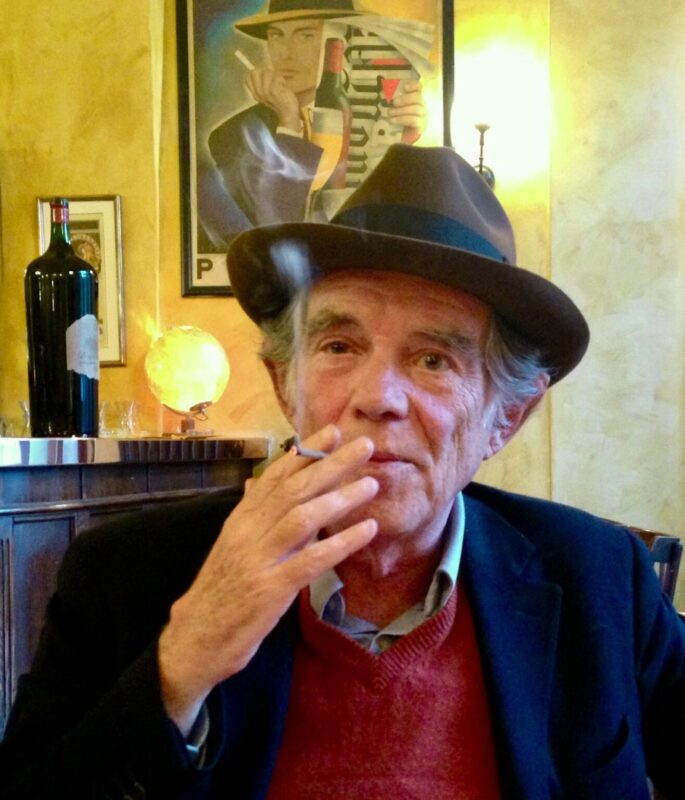

Gianfranco Sanguinetti, 1948–2025

The Prague Mystifier of the Italian Ruling Classes

Gianfranco Sanguinetti, writer, thinker, adventurer, collaborator of Guy Debord and the Situationist International, who in the 1970s drew attention to the crisis of capitalism and state repression not only in Italy, died on October 3 this year at the age of 77. However, few people knew him in Prague, where he spent his last decades.

Gianfranco Sanguinetti in his favorite Prague bistro in 2014. Photo by Karolina Fabelová

“Did you know?,” my friend asked. “The last Situationist lives in Prague.” He was referring to Gianfranco Sanguinetti, who after a crisis in the Situationist International (SI) was the last of its members still closely collaborating with Guy Debord when the two decided to dissolve the organization in 1972. Sanguinetti was also among those who most actively developed Situationist practice in the years following the SI’s dissolution, and he continued working with Debord when most had given up on him, until Debord fell out with him too in the late 1970s. To my surprise, Sanguinetti been living in Prague for decades.

Sanguinetti was more than just the “last Situationist,” if by Situationism we understand a specific, time-bound tendency and a primarily artistic or intellectual mode of engagement. He directly participated in the revolutionary events of the 1960s and 70s in France and, especially, in Italy, where the political tension lasted longer and the leftist upheaval met more brutal State and paramilitary repression. In his writings and actions—including one ingeniously subversive hoax, which could arguably be labeled the last great Situationist act—he uncovered the willingness of Italy’s economic and political elites to approve of the violent provocations of the extreme right, even while it openly sought to coopt and tame the Communist Party, all in the interest of saving capitalism.

Beyond his political engagement, Sanguinetti also found time to devote himself to cultivating wine and olives in Tuscany, to pursuing business deals in the disintegrating Soviet Bloc, and to collecting rare books and erotic art in Prague. His Italian-language Wikipedia entry introduces him as a “scrittore, enologo e rivoluzionario,” that is a writer, winemaker, and revolutionary.

My friend had learned about Sanguinetti from another friend, who subsequently explained to me that the old Situationist preferred not to draw attention to himself. He refused to grant interviews, he made no public appearances, and he seemed satisfied that after years spent in public view and (as I later learned) under surveillance by multiple States, he could live in Prague in relative obscurity. So I hesitated to ask him to join us in a public discussion we were organizing, a meager contribution to today’s slow academic rebellions. But we were celebrating the English-language publication of a book that Sanguinetti had helped publish in French (Karel Teige, The Marketplace of Art, Rab-Rab Press, 2022; published in French by Editions Allia, 2000), and it felt impossible not invite him. In the end, I gave him a call.

He answered kindly that he wouldn’t make a public appearance, but that he might just stop by. On the evening of the event, he entered while the discussion was in full swing. He drew our attention from the back, and when given the chance to speak he waxed eloquently indignant about the capitalism-induced commodification and degradation of art. After the formal event ended, we talked for a while longer, promising each other to meet again soon. He was suspicious of people who wanted things from him, but he was open and generous with those who wanted nothing.

Adventurer from Birth

His mother Teresa Mattei was a prominent Communist, active in the anti-Fascist resistance, and known today as the woman who made the mimosa the symbol of International Women’s Day in Italy. His father, Bruno Sanguinetti, whom Mattei had met through partisan activity, was the heir of a successful industrialist, and he did what all self-respecting heirs to a fortune should do: he used his money to financially support a movement that aimed to turn the wealth of the past into a remade future—in this case, the Italian Communist Party. When Mattei became pregnant while serving as a representative to the postwar constituent assembly, legal complications relating to Bruno Sanguinetti’s previous marriage prevented them from marrying in Italy. Apparently worried about the attitudes of Italy’s conservative elites toward illegitimate children, the couple left to get married in Budapest, where they were helped by contacts among Hungarian Communists. Shortly thereafter—we can only speculate whether the couple was also becoming disillusioned with the Hungarian Communist Party’s then-intensifying machinations to establish one-party rule, in stark contrast to the Italian Communists’ postwar approach to power—they moved again, this time to Pully, Switzerland, on the outskirts of Lausanne, where on July 16, 1948, Gianfranco was born.

Two years after his birth, Gianfranco’s father died in unclear circumstances—according to some, he was killed, possibly for money, possibly for political reasons. In 1955, when Gianfranco was six or seven, his mother was expelled from the Communist Party for disagreeing with the Stalinist line, however moderate, of Palmiro Togliatti.

The young Gianfranco had his first direct run-in with the authorities ten years later, when he was arrested for unfurling the Spanish Republican flag in front of the Francoist minister Manuel Fraga on a visit to the Royal Palace in Milan. More serious confrontations were to come in the ensuing years, when he would repeatedly accuse the State apparatus of violent false flag operations. The first important moment came in December 1969, when a bomb killed seventeen bystanders on Milan’s Piazza Fontana, to which the police responded with mass arrests of anarchists—one of whom died after allegedly falling out of a window in police custody, inspiring Dario Fo’s play Accidental Death of an Anarchist. Gianfranco and his newly founded Italian Section of the Situationist International answered with a manifesto titled Il Reichstag brucia? (Is the Reichstag Burning?), in which they claimed that the most likely figure behind the attack was the State itself. Shortly thereafter, Gianfranco was called before the Milan court, and he considered it an opportune moment to move to Paris. His time in Paris was cut short in July 1971 when, after returning from a trip to smuggle a Portuguese translation of Debord’s Society of the Spectacle into Portugal’s authoritarian Estado novo, he was deported from France back to Italy.

Like many children of Italian Communists, Gianfranco had an ambivalent relationship toward the political positions of his parents. By the 1960s, in spite of deep-seated anti-Communism among the Italian elites, the Italian Communist Party had become firmly established in the very political system that the young generation was rebelling against. When Gianfranco was turning twenty-one, according to his younger brother, he asked his mother for a memento to symbolically mark his maturity. Telling her he wanted nothing that would recall her postwar involvement in establishing the new system, he asked for the gun she used to shoot Fascists. For better or for worse, she declined and kept the weapon enclosed in her dresser drawer.

The Last Chance to Save Capitalism

Gianfranco Sanguinetti was no pacifist, but he probably would have never used the gun he asked for. At a time when many leftist activists decided that State repression and the covertly State-supported violence of the radical right called for a reaction in kind, he rejected terrorism. Later on, after years of direct experience with the repressive organs of the State, he expressed his position most fully in a 1979 text called On Terrorism and the State (Del terrorismo e dello stato), where he argued that terrorism as a tactic of resistance plays into the State’s hands. Even heroic and righteous violence that responds to the violence of the extreme right tends to produce little more than a spectacular image of popular power, reducing resistance to romantic acts of isolated individuals, while allowing the State to justify increasing repression. As Sanguinetti saw clearly during the decade following 1968, it was for just this reason that the State so often tolerated and sometimes directly supported terrorism, while passing it off as the activity of the left.

This principled position against violent adventurism still did not shield Sanguinetti when, in March 1975, the police acted against him more determinedly than before. Stopping him while driving with his then-girlfriend Katherine Scott, the police planted machine-gun ammunition in their car and charged them with terrorism. The Italian authorities were apparently aware that Sanguinetti was up to something (he surmised that they had tapped his lawyer’s phone, possibly due to another of his lawyer’s cases); but they didn’t know that the attack he was planning had nothing to do with guns. He and Scott were on their way to printing a book that a few months later would shake the Italian intellectual establishment: Rapporto veridico sulle ultime possibilità di salvare il capitalismo in Italia (A Truthful Report on the Last Chance to Save Capitalism in Italy).

In the police car on the way to the station—as Gianfranco told us the story from the terrace of his Prague apartment—he surreptitiously took the manuscript from his pocket and passed it to Scott, who quickly hid it in the case of her violin. In the women’s prison the manuscript either wasn’t found, or was simply overlooked as a harmless curiosity. The police conducted repeated raids on Sanguinetti’s house, but after they failed to uncover any arsenal for the coming revolutionary war, they let the two prisoners go.

Sanguinetti was free, but he recognized that he had to be careful. He changed his publication plans and finished the book in secret. He found a publisher who didn’t know the book’s author and didn’t ask about his motives. Once the text was safely in the publisher’s hands, the unidentified author fled Milan.

As I remember the story (which perhaps archival research can eventually confirm or clarify), it was thanks to the good will of the Sanguinetti family doctor, who counted influential mafia bosses among his wealthy clients, that the fugitive was able to flee to Crotone (“the city of Pythagoras,” as Gianfranco liked to call it, recalling the ancient fame of what is now a relative backwater). There he enjoyed the protection of the local leader of organized crime, who out of respect for the doctor never inquired whom he was protecting or why the man needed to hide from the long arm of the law. I imagine the local mafia boss—perhaps wrongly—feeling a primordial solidarity that unites all the outcasts of the earth, regardless of their political visions and personal interests. In any event, before anyone could stop it, the Truthful Report was out in the world.

The dangerous book was no revolutionary tract or work of investigative journalism that uncovered shocking facts. On the contrary, inspired by a conversation with Guy Debord (who later translated the Truthful Report into French), Sanguinetti wrote an explicitly reactionary text whose pseudonymous author “Censor” disdained parliamentary democracy, which he characterized as merely an effective mechanism for maintaining the power of the elites, capable of restraining mass opposition by coopting organizations like the Communist Party. At the same time, Censor proclaimed the usefulness of terrorism, which could spread fear in the populace and justify still stricter social control beneath the illusory democratic veil.

Sanguinetti took seriously the role of the refined grand bourgeois Censor. In baroque sentences full of untranslated French expressions and Latin proverbs, he cited Dante and Petrarch, interpreted Machiavelli, Clausewitz, and Carlyle, and addressed contemporary political issues via deep historical excurses. He had the text set in elegant typography, printed on the highest quality paper, and sent in 520 numbered copies to the most powerful financiers and businessmen, the most influential diplomats and journalists, and the most highly placed representatives of the Italian political order.

The hoax was convincing because Sanguinetti was cultivated the way the Italian grand bourgeoisie only imagined itself to be. As he later noted, “although [the world represented by Censor] still exists, […] it no longer has the strength to produce bourgeois of such lucidity and cynicism.” The real and self-aware bourgeoisie was not capable of saying aloud what it believed or of using arguments that could even convince itself that it was right. When “Censor” gave it the right words, it nodded eagerly.

The great men of Italy discussed Censor’s theses with serious faces, pronouncing the correctness of his allegedly iron logic and arguing over who its ingenious author might be. Only six months later did Sanguinetti himself reveal his deception in a text called Prove dell’inesistenza di Censor enunciate dal suo autore (Proof of the Nonexistence of Censor Presented by his Author). Sanguinetti no longer had to demonstrate that the State authorities and those who controlled them supported terrorism; the Italian elites virtually admitted it themselves by agreeing with Censor’s assessments. Only many years later did evidence come to light definitively establishing that the 1969 bombing at the Piazza Fontana had been indeed the work of far-right terrorists with assistance from within the Italian State, and probably with the tacit support of the CIA.

Like Casanova

Gianfranco Sanguinetti was torn between a commitment to the intense political struggles of the Italian 1970s and a desire to hide from a growing array of potential enemies. In 1974, still before the Truthful Report affair, he withdrew for the first time to the Tuscan countryside, where he devoted himself to growing grapes and olives. He would often return in later years, even after he eventually left Italy to see and do business in the collapsing Soviet Union (where he wanted to see a dying empire, he would later explain), and after he settled in Prague in the early 1990s.

He never got used to Czech cuisine, but he valued the subversive and sacrilegious strand of Czech culture represented by figures like the antiauthoritarian novelist Jaroslav Hašek and the avant-garde theorist and typographer Karel Teige. He was also at home among the shelves of Czech used-book sellers, which in the 1990s must have been a paradise for lovers of old publications and prints. On top of that, the Czech lands had the great advantage of being located relatively far from the center of attention of Italian intelligence services.

It could be said that in his Prague emigration, Gianfranco grew bored. He spent his time with a relatively small circle of friends and an enormous collection of rare books, including first editions of Marx and parts of Karel Teige’s avant-garde library. He read widely, wrote pointed critical pieces when the world angered him enough, and organized his personal archives. In this he was a bit like Giacomo Casanova, who after long adventures across Europe settled into a life of ease in the quiet North Bohemian castle of Dux (in Czech, Duchcov).

Gianfranco himself sometimes noted this similarity—in jest, but not without reason. One would be hard pressed to find in this age someone so close to Casanova in erudition, charisma, mastery of words, and storytelling flair, not to mention his appreciation for the erotic. And yet Gianfranco would shake his head disapprovingly when told by his friends that he should spend his years of Czech leisure like Casanova, who thanks to the end of his excited wandering had time to write down the famous Story of My Life. Gianfranco also definitively ruled out the possibility of a book of interviews. It was hard to tell if he really wanted to be forgotten, or if he hoped for the posthumous recognition of a prophet come before his time.

He concentrated his narrative efforts on those around him, interspersing the stories of his days defending protesters and annoying the bourgeoisie with citations from the romantic philosopher-poet Leopardi or the anti-Fascist philosopher Giuseppe Rensi. With incomparably eloquent vulgarity he cursed at the baseness and rottenness of the world. With sudden tenderness he spoke of what he missed from Italy, whether it was the works of Michelangelo or his family vineyards.

If I’m right in believing that the only true patriot is one capable of swearing at his own land, then Gianfranco was a true citizen of the world, because he swore at all lands, and he loved them all. When I wrote to him once while I was staying for a time in Budapest (to conduct research into the history of the idea of internationalism), he answered with a quote from an old anarchist “Song of Exile” (“Stornelli d’esilio”):

Our homeland is the entire world

Our law is freedom

In July of this year I learned that Gianfranco had been hit by a car, the worst invention in human history. I last saw him at the clinic where he was slowly but successfully recovering, but soon after that visit he fell ill, and his weakened body gave in.

He lived more than would fit into a hundred ordinary lives, especially in this quiet country in what has, for quite some time here, been a rather boring age. But we may be soon visited by a more uncertain time ripe again for heroism. I hope we find the courage to respond as Gianfranco Sanguinetti did, with refined humor and radical cultural action that can wound the powerful more deeply than guns.

The author is a philosopher and anthropologist.

The article first appeared in Czech in A2 23/2025. The english translation, made by the author, was published in Communis on November 26, 2025. A2 publishes the translation with the permission of the author and that of Communis.